The Best Makerspace is at Home

A makerspace could just be your home; any time you are activating your curiosity, fixing something around the house, cooking a meal for the family, or even doing your chores.

This week’s article comes to us from Sofya Zeylikman. She’s a Boston-based design researcher, Harvard alumna, and makerspace enthusiast.

When someone asks me “What is a makerspace?”, I typically give the quick answer “It’s usually an open lab space with equipment like a 3D printer, laser cutter, etc where folks can learn how to build things”. I know that most people now have a concept of the typical STEM-centered makerspace that has likely opened up in their kid’s school or library, so I find it easier to give that response.

I wish I didn’t have to answer that way since that’s not really how I would think of “making” or what a makerspace needs to be called a makerspace. A makerspace could just be your home; any time you are activating your curiosity, fixing something around the house, cooking a meal for the family, or even doing your chores.

Why read this article:

Parents: While I don’t have first-hand experience raising kids during a pandemic, I hope this article helps you think of ways in which you can cultivate a culture of making, right in your own home.

Educators: I hope that this might help you think of some non-obvious ways to encourage a maker’s mindset-- especially if you are not in the STEM/STEAM fields

Everyone: I believe in the joy and satisfaction of cultivating a practice of “making”, and I hope this article inspires you to try something new.

------

How I Got Started

I recently moved into a new apartment, and I found myself getting really caught up in decorating my room. Now that we all spend so much time at home, it feels like an act of self-care to get the right kind of bedsheets and matching furniture sets.

One of the last pieces that really pulled my room together was this large mirror with a brass frame. It’s pretty heavy, so it required anchoring it to the wall.

Luckily, I had spent much of my childhood following my dad around as he fixed up different parts of our house. Sometimes he’d be fixing a broken toilet, other times he’d be spackling up some drywall, or tending to the garden.

When I was around 8 or 9, he taught me how to use a drill so that I could help him put up some shelving. He explained to me that if I ever wanted to put up a shelf, I had to locate the wooden studs to screw into, and get these plastic anchors that would keep the drywall from breaking.

These small projects at home, along with a tradition of knitting and sewing that was passed down to me by my grandmas, shaped my interest in “making” all throughout my childhood and into adulthood.

------

Am I a Maker?

It’s no surprise I ended up studying Furniture Design in college, working at an academic makerspace for two years, and getting a Master’s degree in Education with a focus on personalized learning in makerspaces. What may be surprising is that I often struggle with identifying myself as a “Maker”-- and the activities that I enjoy as “making”.

Dr. Chachra’s piece, “Why I Am Not a Maker” articulates how I feel better than I could myself.

“The cultural primacy of making, especially in tech culture—that it is intrinsically superior to not-making, to repair, analysis, and especially caregiving—is informed by the gendered history of who made things, and in particular, who made things that were shared with the world, not merely for hearth and home.”

All throughout my childhood and adolescence, I was learning by creating, and I had no idea. So it is hard for me to think of these activities as they fit into the larger Maker movement which tends to focus on tech culture, and “making” as an activity that involves 3D printers and expensive materials. My family immigrated to the United States in the late 90’s, and I grew up in a “working-class” household for much of my childhood. While my sister and I lived with far more luxuries than my parents and grandparents had, we were often reminded of their struggles and resilience.

“Working-class folk have not had the luxury of discovering making and tinkering; they’ve been doing it all their lives to survive- and creating exchange networks to facilitate it. Somebody across the street or down the road is a mechanic, or is wise about home remedies, or does tile work, and you can swap your own skills and services for that expertise”- (Vossoughi, Hooper, & Escudé, 2016, p.212)

In my home, I was lucky to be learning intrinsically through my family. While helping my dad around the house, I was learning how all of these built objects around my house worked. I learned what was inside of the walls, how the electricity ran, as well as more intuitive skills like how to mark and measure materials that weren’t perfectly flat or square.

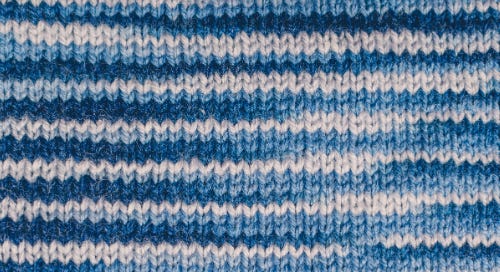

At the same time, I had learned to knit, crochet, and sew from my grandmothers and my mom. I learned how two-dimensional pieces of fabric come together to create three-dimensional pieces of clothing. I also learned patience and how to fix stitches if I made a mistake. Over time, knitting and crocheting for me has become a form of meditation where I can slow down and focus on something outside of the screens I stare at every day.

-----

Why the home might be the perfect place

Whether or not you have access to the equipment traditionally found in makerspaces, I’d encourage you to shift your focus to your home. How might you cultivate your own making practice with the tools, materials, and challenges already present at home? How might you share your practice with others inside the home, and with your local community?

It turns out that my experience of cultivating a maker’s mindset from my family members while engaging in activities at home is similar to those of youth today. A recent study surveyed minoritized youth in Chicago to better understand how making is supported in homes outside of the dominant culture.

“That is, through surveys and interviews, participants identified the home (in lieu of other more traditional learning settings) as a primary place for learning and making activities done in collaboration with family members. Additionally, at home, youth reported having access to materials, tools, their own free time, and help from family members and their wider family-based networks.”

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1255127.pdf

The article further explains how the relationships between youth and their family members were key to supporting their engagement with making. Making can be encouraged by family members in a more explicit way, in which parents and their children are creating together, but also in more subtle ways.

“Notably, Joseph did not mention actively participating in making with his father; when a parent is active in maker activities in the home, even if they are just acting as a model, those practices may be visible to the youth and leave open potential opportunities for the development of interest, pointing toward “observation with intent” [41]. This observation may be a first step toward leading youth to engage in legitimate peripheral participation and full participation within a community of practice [22].https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1255127.pdf

------

Some steps to cultivate making at home

Start with yourself (Interests):

What are your interests or creative practices? Is there something you’ve been meaning to get done around the house and fix? What about your community- is there a need in your community for clothes, masks, or food?

For example, I have recently started a sourdough experiment and found online figure drawing sessions through Zoom. If I had a sewing machine, I’d likely be sewing up face masks for the changing seasons!

What’s important is to find whatever feels authentic to you, and that you’re intrinsically motivated to do! The more that you are excited about an activity, the more likely you are to sustain the practice and share with others. The goal is to create a home where connected learning happens.

Expand your network (Relationships):

Recently, I was on a video call with my mom as she showed me a dress that she sewed to wear to work (from home). Even as an adult, I enjoy connecting with my parents over projects we are working on. I still learn from her about pattern-making and how she was able to modify the pattern to fit her body better. I showed my mom some of my recent drawings, and we reminisced over my crafting projects as a child.

I’ve also entertained my roommates by showing them my new “pet”, or sourdough starter. It’s been an interesting experiment to learn more about fermentation and what conditions need to be met for the starter to properly bubble up. While I took on this experiment on my own- it’s been fun to share my struggle with getting the fermentation schedule right, and troubleshooting out loud. We pooled some resources together, and I’ve crossed my fingers hoping a heating pad and some patience will give me my desired result!

What are some ways that you might include others in your practice of making? Maybe it’s as simple as a phone call to a family member or friend. Perhaps it’s sharing the results of your making (in my case a future loaf of bread) with your home/community? Or maybe it’s more formal, and a way to teach others a skill you have mastered.

The goal is to embed learning into a routine or hobby around the house that keeps you motivated, and connects others to become curious and learn from you.

Repeat! (Opportunities)

As you continue to practice making at home, and try new things, you may discover untapped opportunities for your own personal future, or open up possibilities for those around you.

I am passionate about education because of its ability to open up doors for possibilities you may not have thought of for yourself. Through the lessons learned by making at home, you may spark a potential career path, or side project that matches your unique skills.

“For an illustration of these practices, let’s return to our cyclist. Initially motivated by the joy of riding, through ongoing observation and experience, our cyclist slowly builds an appreciation for the design of the object (her bike) as well as the associated systems connected to bike riding. She interacts with the numerous components of her bike and begins to consider it as a whole as well as a myriad of subsystems: gears, brakes, tires and wheels, and a variety of safety features. Complexity ramps up as she investigates the many external systems she interacts with each time she rides: bike lanes, traffic patterns, pedestrian crossings, etc. She makes informed observations about how her bike and biking systems are functioning, and finally begins to recognize opportunities for redesign—of the bike itself or the many internal or external systems within which her bike is situated.” -- http://www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Maker-Centered-Learning-and-the-Development-of-Self_AbD_Jan-2015.pdf

Key Takeaways:

Makerspaces do not have to be found in engineering classrooms or filled with 3D printers. You can cultivate your own practice of making at home with materials you already have.

Begin with your own interests and needs. What are you intrinsically motivated by?

Build a community around your practice. How might you share your passions, learnings, and challenges with others?

Find Opportunity. Reflect on how you might continue to pursue your passions in other areas of your life.

Sofya is a senior design researcher for athenahealth. She led the CEID Design Lab at Yale, is a graduate of the Technology, Innovation and Education, Ed.M Program at Harvard and has studied furniture design at the Rhode Island School of Design. Sofya is passionate about the way that design and education shapes our world.