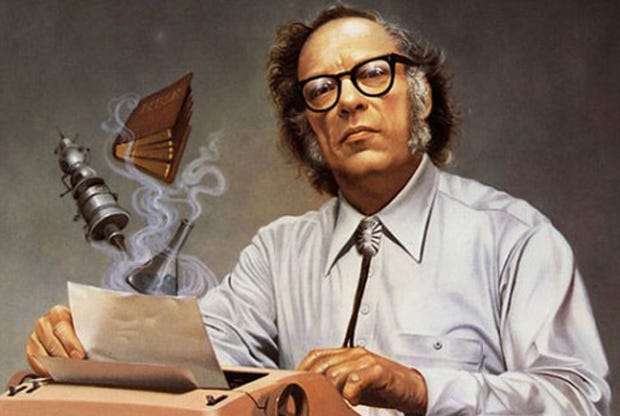

All science fiction fans are bound to have read through the writings of Isaac Asimov. For those who know nothing about him, he was a prolific author of science fiction and science books. He is said to have written over 500 volumes of work in his lifetime. Most famous are his Foundation and Robot series. He was a biochemist and author.

I stumbled upon his book ‘Foundation’ when I was in high school. The fictional world of mathematician Hari Seldon, who invents the field of psychohistory - a combination of psychology, science, and mathematics. In a few years, I had read all of the Foundation series, all of the Robot series and by today have read over 100 of his books and collections of short stories.

You can read more about him online, but this isn’t just about his writings. At Upepo I’m trying to understand what happens early on in the lives of these incredible people.

Down the rabbit hole, last week I stumbled upon his book “The Early Asimov - 1” where he reminisces and draws upon his journal entries over the years as he began his career as a writer. What stood out to me, in particular, were his early experiences with rejection.

Let’s look closely at where he started

Early Years

I began to write when I was very young-eleven, I think. The reasons are obscure, I might say it was the result of an unreasoning urge, but that would just indicate I could think of no reason. Perhaps it was because I was an avid reader in a family that was too poor to afford books, even the cheapest, and besides, a family that considered cheap books unfit reading. I had to go to the library (my first library card was obtained for me by my father when I was six years old) and make do with two books per week. This was simply not enough, and my craving drove me to extremes. At the beginning of each school term, I eagerly read through every schoolbook I was assigned, going from cover to cover like a personified conflagration. Since I was blessed with a tenacious memory and with instant recall, that was all the studying I had to do for that school term, but I was through before the week was over, and then what?

So when I was eleven, it ocurred to me that if I wrote my own books, I could then reread them at my leisure. I never really wrote a complete book, of course. I would start one and keep rambling on with it till I outgrew it and then I would start another.

This shows that something incredible happened between the ages of six to eleven. An interest not only developed but grew stronger and turned into an obsessive habit. The writing was a way to read more, not just a way to write. I shudder to imagine what would have happened if his parents asked him to stop wasting time writing and reading nonsense and focussed on test-prep instead. :)

Young adulthood

It was not until May 29, 1937 that the vague thought ocurred to me that I ought to write something for professional publication; something that would be paid for! Naturally it would have to be a science fiction story, for I have been an avid science fiction fan since 1929 and I recognized no other form of literature as in any way worthy of my efforts.

These reflections really astonish me. He never set out to be an author. He wrote because he enjoyed it. The ‘wanting to be professionally published’ was an additional thought that crept in many years later. Let’s see how that first endeavor turned out.

The story I began to compose for the purpose, the first story I ever wrote with a view to becoming a ‘write’, was entitled “Cosmic Corkscrew.”

I wrote only a few pages in 1937, then lost interest. The mere fact that I had publication in mind must have paralyzed me. As long as something I wrote was intended for my own eyes only, I could be carefree enough. The thought of possible other readers weighed down heavily upon my every word. So I abandoned it.

The movies rarely show you this side, do they? There were no villains here, no one who laughed at the idea of him being an author and kicked him to the curb. The writing never came naturally and it was abandoned for a while. It’s not until a whole year later that this journey resumed.

Early Rejections

After making a trip to a publisher to find out about an issue of “Astounding Science Fiction” magazine that didn’t reach him on time, Asimov found out that the schedule had changed by a few weeks. This gave him some relief and comfort and reactivated his desire to write and publish.

The near brush with doom, and the ecstatic relief that followed, reactivated my desire to write and publish. I returned to “Cosmic Corkscrew” and by June 19 it was finished.

The next question was what to do with it. I had absolutely no idea what one did with a manuscript intended for publication, and no one I knew had any idea either. I discussed it with my father, whose knowledge of the real world was scarcely greater than my own, and he had no idea either.

How refreshing! We assume that people who go on to do great things have superhuman confidence and are always out to prove detractors wrong. This clearly shows that despite writing, he had no idea what to do with it and neither did his family. What had occurred to him then was to go back to the publisher he met a few weeks back and submit the writing to him.

Why not repeat the trip, then, and hand in the manuscript in person? The thought was a frightening one. It became even more frightening when my father further suggested that necessary preliminaries included a shave and my best suit.

I was convinced that, for daring to ask to see the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, I would be thrown out of the building bodily, and that my manuscript would be torn up and thrown out after me in a shower of confetti.

The imposter syndrome many of us feel is not new or abnormal. It’s normal and it’s okay.

Trying to mask panic, I asked to see the editor. The girl behind the desk spoke briefly on the phone and said, “Mr.Campbell will see you”

He told me about himself, about his pen name and about his opinions. He also promised to read my story that night and to send a letter, whether acceptance or rejection, the next day. He promised also that in case of rejection he would tell me what was wrong with it so I could improve.

He lived up to every promise. Two days later, on June 23, I heard from him. It was a rejection. (Since this book deals with real events and is not a fantasy-you can’t be surprised taht my first story was instantly rejected.) Here is what I said in my diary about the rejection: “At 9:30 I received back ‘Cosmic Corkscrew’ with a polite letter of rejection. He didn’t like the slow beginning, the suicide at teh end.”

Campbell also didn’t like the first person narration and the stiff dialog, and further pointed out that the length (nine thousand words) was inconvenient - too long for a short story, too short for a novelette.

It’s rare to hear back a meaningful rejection anymore. Reviewers go out of the way to make sure their comments are not available for applicants in many cases - lest it gives you a competitive edge. And that means people repeatedly apply with no way of knowing how to improve or what is needed. A kind, useful rejection is one of the most powerful tools of change in the universe.

The pleasant letter of rejection - two full pages - in which he discussed my story seriously and with no trace of patronization of contempt, reinforced my joy. Before June 23 was over, I was halfway through the first draft of another story.

Many years later I asked Campbell why he had bothered with me at all, since the first story was surely utterly impossible.

“It was,” he said frankly, for he never flattered. “On the other hand, i saw something in you. You were eager and you listened and I knew you wouldn’t quit no matter how many rejections I handed you. As long as you were willing to work hard at improving, I was willing to work with you.”

The next rejection was perhaps even more vital in the making of Asimov.

Besides, before the month was out I had finished my second story, “Stowavay,” and I was concentrating on that. I brought it to Campbell’s office on July 18, 1938, and he was just a trifle slower in returning it, but the rejection came on July 22. I said in my diary concerning that letter that accompanied it:

“…It was the nicest possible rejection you could imagine, Indeed, the next best thing to an acceptance. He told me the idea was good and the plot passable. The dialog and handling, he continued, were neither stiff nor wooden(this was rather a delightful surprise to me) and that there was no one particular fault but merely a general air of amateurishness, constraint and forcing. The story did not go smoothly. This, he said, I would grow out of as soon as I had had sufficient experience. He assured me that I would probably be able to sell my stories but it meant perhaps a year’s work and a dozen stories before I could click…”

The anatomy of this rejection letter is wonderful :

Kind

Focussed on the writing

Not personal

Clearly broken down

A path to getting better

Assuring

The book goes on with more details and perhaps a lot of it is 20-20 hindsight.

However, it shows the power of carefully nurtured, early hobbies aided by gentle helpful rejection in the making of titans.

Do you know of more such stories of gentle, helpful rejections? Can you guide us?

Have a playful weekend,

Prasanth

Sources:

Prashanth

This is quite an inspiring read. I'm a great believer in kind, direct and specific feedback. Learning to give it requires tremendous patience and trust in self and learning to receive and act upon it requires tremendous growth mindset.

I especially loved the way Asimov saw the feedback as an improvement over the previous one. It clearly shows where his focus was - on his writing and on his process.